“Roll Tide, Stream Nicki”: How BamaBarbz Started A Campus Phenomenon

October 13, 2021

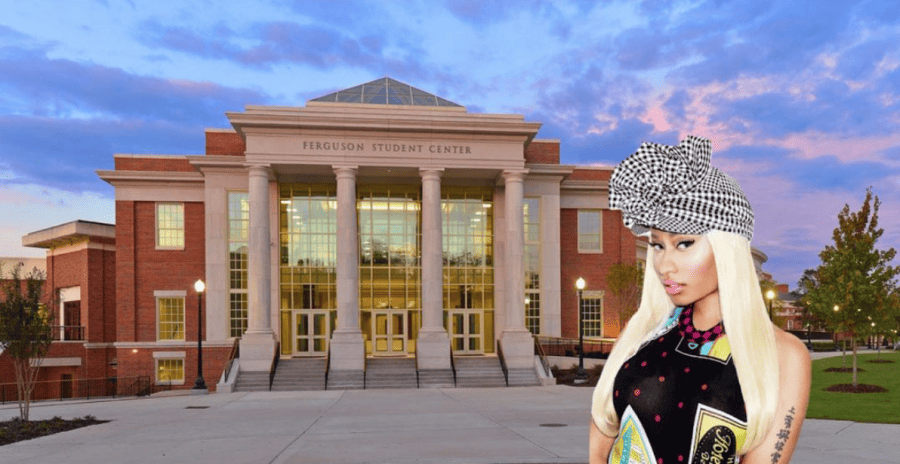

On April 22, Carson Lott, a UA freshman majoring in economics, created a Nicki Minaj stan account on Instagram called @bamabarbz.

The account was inspired by @emorybarbz, a similar account created at Emory University. It started out with a few simple memes of Nicki Minaj photoshopped in front of UA buildings. By the end of the summer, the page had over 1,000 followers, spawned other fan accounts and partnered with Icon, Tuscaloosa’s only LGBTQ bar, for a themed night.

“I didn’t really expect for it to get the kind of traction that it did, but this campus is more diverse than it seems from just the pamphlet,” Lott said.

This collection of UA-centered fan accounts is a product of the larger movement that is internet stan culture: communities of committed super fans spanning social media platforms, especially Twitter.

They identify themselves with monikers tied to a certain artist, like Barbz for Nicki Minaj, Swifties for Taylor Swift and Pharbz for Phoebe Bridgers. Aside from the toxic elements these fanbases can take on at times, including organized harassment, bullying and body shaming, they bring together a shared cultural understanding and perspective that has infused with a unique Alabama flair to create a new and vibrant community on campus.

“It’s special because it’s so different from what you would view The University of Alabama as,” said Valerie Allen, a freshman majoring in musical theater and the creator of @uapharbz, a Phoebe Bridgers stan account. “Coming in, I thought I would be very outcasted and alone, but when I saw these accounts and made my own, I realized there are way more people like me.”

Online stan communities have common traits: inside jokes, shared language and phrases, even certain political worldviews. These qualities foster the unique connection and culture shared between those within them.

“Even though there’s not that many people following my account, there’s a lot of people following these same three accounts. It’s so interesting that there’s just a lot of people who have the same interests, humor, everything as I do,” Allen said. “I’m just not alone making these stupid jokes; it’s fun.”

This like-minded community of Phoebe Bridgers fans was seen last week when Bridgers performed at Avondale Brewing Company in Birmingham, Alabama. Even with impending thunder and dark skies, hoards of fans from as far away as Nebraska gathered in a line that wrapped around the entire block and down the street.

Avy Whaley, a senior majoring in business, drove herself and her two friends from Tuscaloosa to Birmingham to see Bridgers.

The desire to meet like-minded people on campus — especially after a school year of virtual learning — was the primary motivation for Camryn McGaha, a sophomore majoring in criminal justice, to create the @bamaswifties account, a Taylor Swift stan account.

“The past year has been very bad for most people. Freshman year during COVID was not good,” McGaha said. “Music is very personal, and I think if you relate to someone’s music, you’ll probably get along.”

Stan culture around these specific fanbases is also tied to LGBTQ culture. Much of the terminology and aesthetics seen in modern stan communities can be traced specifically to Black queer culture.

This connection goes back decades to artists such as Judy Garland, who had a massive following from the LGBTQ community. Today, it has even further ingrained itself in pop music, with Lady Gaga, Britney Spears and Nicki Minaj having massive fanbases in queer spaces. It is this connection that, in part, led to the first “Barbz Night” at Icon in August.

“We had been interacting on Instagram for a while, and they had talked about doing a Barbz dance,” said Kyle Richardson, Icon’s owner. “So I said, ‘What about a Barbz night at Icon?’ and it just took off from there.”

Since then, Icon has hosted a Swifties night and two Barbz night events. For the most recent Barbz event, Lott and Richardson used the cover charge collected at the door as a charity fundraiser. In total, they raised $500 for the Campaign for Southern Equality, an LGBTQ-centered charity that advocates for civil liberties, conducts grassroots community organizing and provides health care resources throughout the South.

Richardson attributed the success of the events to the community that the accounts built. The accounts and their connections to Icon and the LGBTQ community have created a place for expression for those who are underrepresented on the University’s campus at large.

“I really didn’t know how many gay people went here,” Allen said. “There aren’t really many safe or diverse spaces here. Icon is one of the only places you can really go and be openly gay with your openly gay friends.”

Lott, McGaha and Allen all said they were surprised but incredibly proud of the widespread reception the accounts have received. They all recounted stories of being recognized or approached on campus by people they had never met, excited to finally meet the person behind the Instagram page.

Related accounts from universities across the country have followed and interacted with them, from the University of Montevallo in Alabama to schools in Michigan or Washington. Together, they have formed a united and connected community made up of thousands of people.

“We created a sort of counterculture, but I don’t feel I have any ownership over it. It belongs to all of us,” Lott said. “Roll Tide, stream Nicki.”

Carson Lott is no longer affiliated with Bama Barbz.

Questions? Email the Culture desk at [email protected].