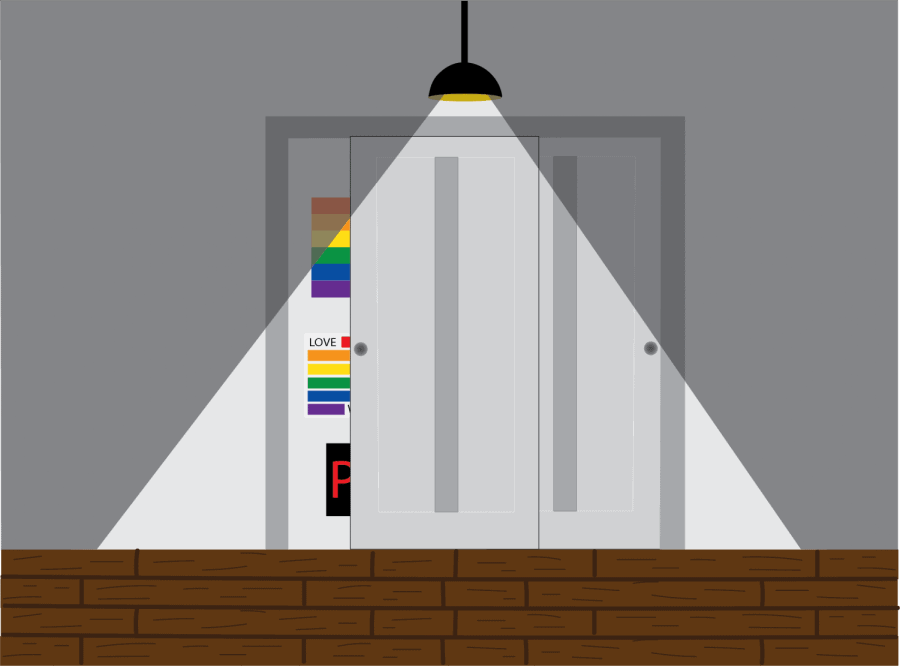

The complications of coming out

July 2, 2021

As our timelines turned rainbow last month in celebration of Pride Month, LGBTQ+ people celebrated and highlighted queer voices that have strived to create change.

While Pride Month can be a time for some to loudly proclaim their identity, for others who don’t feel ready or have decided against coming out, the extroverted nature of Pride Month can add intense pressure and create feelings of isolation.

Coming out can be complicated. Those who encourage queer loved ones to come out before they are ready may have good intentions, but they can do more harm than good — especially when someone is outed without their consent.

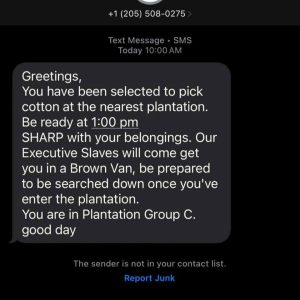

According to the Human Rights Campaign, 2020 proved to be the deadliest year on record for transgender people due to the number of anti-trans hate crimes that took place. In an age when anti-LGBTQ+ legislative proposals continue to target the rights of queer people, forcing people to come out before they are ready could be deadly.

It is important to remember that the experience of coming out is subjective to the individual and their circumstances. For some, coming out can be a beautiful experience and one of the most exciting, liberating times of their life.

Ali Barskiy, a UA sophomore majoring in marketing and economics, said she feels lucky to come from an accepting family because it made coming out as bisexual easier.

“My most important connections never felt threatened because of my identity,” Barskiy said. “I originally came out during Pride Month, and it was the first time I was really letting myself be who I wanted to be. Now, Pride Month means seeing friends of mine talk about supporting my community publicly and seeing how society has changed.”

In a perfect world, all queer people would be met with this same love, acceptance and support at their chosen coming-out time. Some might even argue that in a perfect world, we wouldn’t adhere to heteronormative standards that push the need for people to come out in the first place.

Unfortunately, this is not the case for all queer people. For some, coming out can have extreme consequences ranging from social ostracism and fear of assault to financial insecurity or homelessness.

According to True Colors United, LGBTQ+ youth are 120% more likely to experience homelessness than their non-LGBTQ+ peers. About 40% of the 4.2 million adolescents who experience homelessness in the United States are LGBTQ+ even though LGBTQ+ people only make up 7% of the adolescent population.

Casey Buisson, a UA sophomore majoring in social work, said his coming out meant being forced to give up important positions in his religious community.

“[After coming out], I was told that I would no longer be able to volunteer or work, especially with kids,” Buisson said. “I was the most active member of our youth group. Just a few weeks before, I was one of the people in charge of almost 100 kids from infants to preteens, and all of a sudden, I wouldn’t be able to see any of them again. At first, I was heartbroken. My home didn’t feel like my home anymore.”

A UA senior majoring in political science who chose to remain anonymous said he fears coming out to his family because, for him, coming out could threaten his way of life.

“In the event I came out to my family, a financial punishment would be the first part of the control they would attempt to try to take over me,” he said. “They would take away their support of me to bully me into changing.”

These worries constantly follow young queer people as they embark on their journeys of self-discovery.

“I originally was reluctant to come out because I’ve lived in the South my whole life and heard other people have such poor experiences so close to my hometown that I just couldn’t imagine that being me,” Barskiy said.

After coming out, there is still much left to be discovered, along with new pressures for queer people to slip into labels that sometimes are more limiting than liberating.

“I don’t love [labels], but I use them more for the ease of others than anything else. ‘Gay man’ is much easier to swallow for most people, especially my older parents,” Buisson said. “It gives them something to hold on to and understand, and even if it’s not fully understanding, it’s better than confusing them.”

Many rack their brains to find the right words to describe their sexuality or gender when, in reality, LGBTQ+ identities are multifaceted.

“You can change labels and identities. You get to choose what you disclose and to whom, and you make the rules about this thing,” Barskiy said. “You can pick whatever labels you want, and they might change, but that’s okay. Switching labels doesn’t mean you weren’t valid before; it just means you’re learning and growing.”

Coming out is a road with many twists and turns. While some are afforded the option of coming out, it doesn’t mean they’re any more validated in their identity than those who turn against the traditional concept of coming out. Placing such a primary focus on coming out blindly disregards the harsh reality one may face for being vulnerable in this way. At the end of the day, it’s nobody’s decision to make but the individuals.

“I wish people, both in and out of the LGBT+ community, knew that we still have a long way to go and that the advancements we’ve made are not true for everyone,” Buisson said. “There are so many people out there in our community that are fighting for their lives. LGBTQ+ people of color, women, transgender people, disabled people [and] those in foster care or living on the streets do not get to enjoy pride the same ways that we do.”

By fighting to solve these issues, Buisson said the LGBTQ+ community is working to create a world where people can express their identities freely and safely.

“There are bills in the country right now trying to pass or have passed in just these past few months targeting (LGBTQ+) rights,” Buisson said. “These bills affect people at UA. Students at UA are still fighting, and it is our duty to stand with them.”

If you are in need of resources on campus to educate yourself or seek assistance, available options include the Counseling Center, the Women and Gender Resource Center and the Safe Zone, along with off-campus resources such as Druid City Pride, the Tuscaloosa SAFE Center and The Trevor Project.