Our View | A diverse future hinges on UA recognizing its history

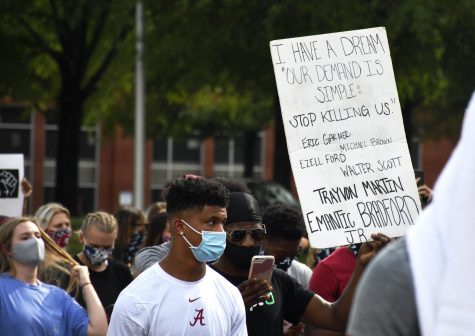

Black history has been botched, minimized and controlled for centuries – a practice that only perpetuated beliefs of Black inferiority. Black History Month challenges us all to pay homage to the trailblazing journeys that Black individuals have conquered through the years.

But why stop at just a month? These buried names, inventions and cultural contributions should merit proper acknowledgement year round. After all, we’ve got a lot of catching up to do, especially on our own campus.

Enslaved Black people built this University, and they kept it running. After making tiresome treks from Marrs Spring to supply white students with water, they slept on floors or the stoops of dormitories because they were forbidden their own beds. Some acted as teaching assistants and went uncredited for major academic accomplishments. Others bear stories too dark for print.

Much of that history has stayed buried deep in the University’s archives, until it was unearthed by Black faculty. Research done by Hilary Green, an associate professor of history in the Department of Gender and Race Studies, is responsible for much of what we now know about the University’s past. But that isn’t to say that the University’s history of white supremacy has been difficult to spot.

In February 1956, when the University first opened its doors to a Black student, it failed to protect her from violent white mobs. Instead, Autherine Lucy Foster ended her third day of school in the back seat of a patrol car as she was escorted to the safety of a nearby barbershop.

It took nearly 60 years for the University to officially acknowledge Lucy Foster’s courage and contributions, first with a clock tower built on the far end of campus and then with a historical marker. In sweltering September heat, officials invited dozens of community leaders to witness the unveiling of the sign outside Graves Hall, which acknowledged the “tumultuous demonstrations” that Lucy Foster had braved. Black student activists led the charge to honor Lucy Foster’s memory, but they weren’t invited to the celebration.

This year, on the 65th anniversary of her enrollment, Foster’s contributions were again minimized, relegated to three sentences and a linked video at the bottom of an emailed newsletter – the first mention of Black History Month by the University’s president.

The University administration’s relationship with Black history is continually hit and miss. The UA System Board of Trustees put together a committee to identify campus buildings that should be renamed. But when the opportunity arose to rename those buildings after prominent Black Alabamians or other worthy alumni, the committee didn’t take that final step. So instead of having buildings on campus with names that honor the history of Black contributions to the campus or the state, we have buildings with placeholder names like the English Building and Honors Hall.

Maybe the University will do its research and get around to nailing a new name to the doors of that buttery brick building with the word “English” slapped on the front of it. But if that’s the plan, they certainly haven’t found the time to keep students updated on its progress.

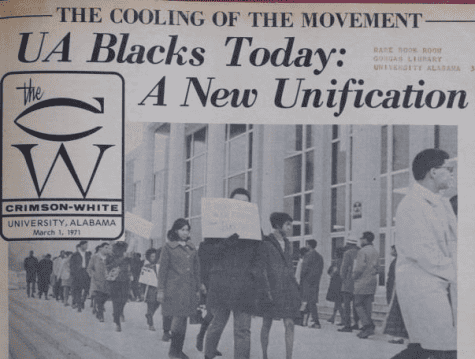

And we would be remiss if we didn’t acknowledge our own place in this silencing. The Crimson White has historically undercovered and misrepresented Black students and their stories. We’ve devoted thousands of pages to white Greek affairs, while only covering Black students and faculty in times of controversy or conflict. Black history deserves recognition even if our University leaders – and sometimes even student leaders – fail to acknowledge it beyond the month of February.

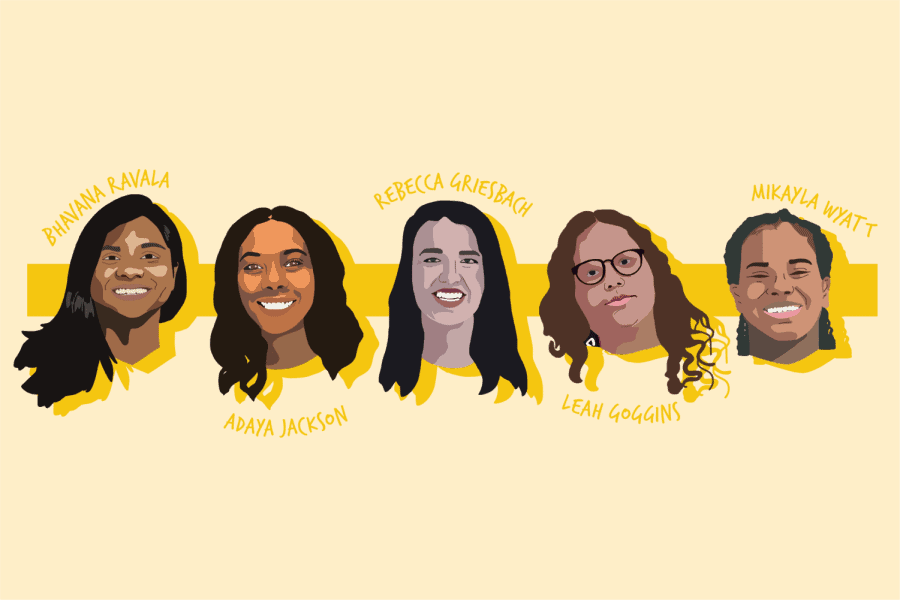

The 2020-2021 Crimson White Editorial Board is composed of Editor-in-Chief Rebecca Griesbach, Managing Editor Leah Goggins, Engagement Editor Adaya Jackson, Chief Copy Editor Bhavana Ravala and Opinions Editor Mikayla Wyatt.