One Million Workers: The unsung heroes of Election Day

Poll workers across the country will wake up bright and early on Tuesday morning, ready to help voters navigate Election Day.

Read more from the Nov. 2 Election Edition.

Each year, millions of first-time voters line up at polling stations to cast their ballots. This experience can send gleeful shock waves through the body, but it can also cause anxiety and stress. But whether a new voter is fretting over forgetting a ballpoint pen or upset by messing up their ballot, poll workers are there to offer support and guidance.

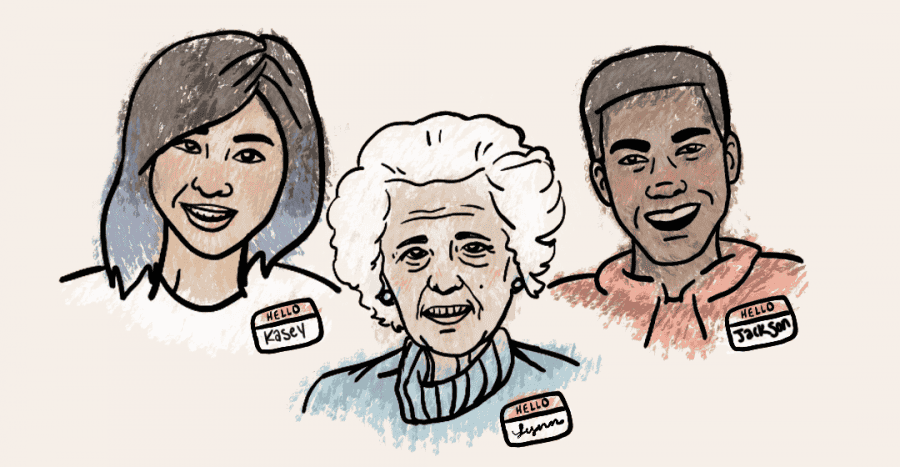

Though over half of poll workers are 61 or older according to a 2018 Pew Research Center survey, these heroes come in all ages.

In fact, in many states, a person can be a poll worker from as young as 16 years old. To sign up, a person needs to check their state’s guidelines for age, residency and voter status, and then contact the election office of the specific town.

“I wanted to be involved politically, and I was part of The League of Women Voters, so they pushed me to sign up to be a poll worker,” said Mallory Rogers, a senior in high school from Georgia who worked the June primaries and the state’s August runoff and also plans to work Nov. 3.

Marguerite Handley, an 88-year-old woman from Etowah County, Ala., started poll work in the late 1990s, when she was 60-years-old. She was a poll worker for more than 15 years until her regular voting station changed.

“I was asked by a friend, and I thought it’d be a good thing to do,” Handley said. “I had never done it before, and I thought someone had to do it so it might as well be me.”

Many poll workers are introduced to the job by friends and organizations like Rogers and Handley.

“Two days before the primaries, I was at a Black Lives Matter protest, and they announced that they needed more volunteers for the primary. I signed up on Monday and worked on Tuesday,” said Zach Plants, a 22-year-old masters of divinity student at Emory University.

Poll working can look different on any given election cycle, and, as Handley explained, it usually takes notable politicians or controversial amendments to drive people to the polls.

“One year the only people who voted were the poll workers and their spouses,” Handley said. “I thought that was really sad. I believe all of it is important, but I found out that not everyone thinks so through this experience.”

On the other hand, in June, Rogers worked a 15 hour day.

“I showed up at 6 a.m., and I was terrified because I hadn’t received training due to COVID-19 and I had never worked the machines before,” she said.

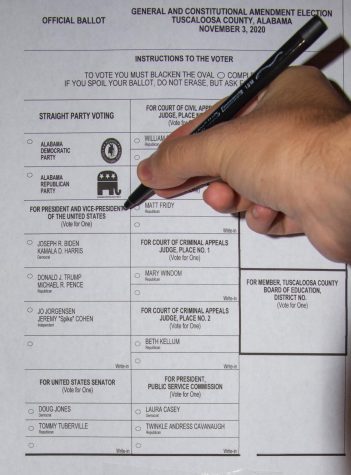

At the polling place where Rogers works, broken machines and a slew of would-be absentee voters slowed down the process. The number of voters who wanted to cast provisional ballots after not receiving their absentee ballots in the mail surprised Rogers.

“We had to direct almost 15 people to the Board of Elections before we received affidavits for people to sign,” Rogers said. “We also had to extend our hours to allow everyone to vote who wanted to. It was a discouraging experience for many of my friends and me, but I believe that through the bad there is always a positive outcome.”

One of the positive changes that Rogers saw in Georgia was the hiring of additional bilingual poll workers and increasing the amount of training offered by the Board of Elections office in her hometown.

In Tuscaloosa County, there are 54 election day sites that need around 366 election day workers. Nationwide, there are over one million workers needed. Despite the slow days and malfunctions, Rogers and Handley both said they would encourage others to sign up to poll work.

“It is really an empowering experience because we got to help people use their voice and vote,” Rogers said.

Plants said another reason people should sign up is because “it’s a civic duty.”

“You gain a deeper respect for the system, even though at times it can be frustrating, it really does humble you,” Plants said.

Poll workers are needed to set-up polling stations, sign in voters, issue ballots and close polls at the end of the day.

“I went in thinking that I would just hand out stickers,” Plants said. “But in reality, I ended up setting up machines and checking people in. It was totally different than what I thought it would be.”

Without these heroes’ commitment to their communities, in-person voting would not be possible.

“If you are even considering being a poll worker in the slightest, you should sign up and try it,” Handley said. “I would say that it is something that everyone should do at least once in their life.”