Opinion | It is time to rename B.B. Comer Hall

October 26, 2022

If you stand on the front colonnade of the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery, you stand in the same place Jefferson Davis stood as he took his Oath of Office to become the President of the Confederate States of America. It is also the same perch from which George Wallace’s voice asserted, “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

But if you take a moment to look up from the plaque commemorating Davis, and look down Dexter Avenue, a radically different picture is painted. You see the spot where the march from Selma to Montgomery ended, where Martin Luther King Jr. said, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” A bit further down the road you can see the corner where Rosa Parks stood as she waited for the bus every day to go home from work.

Alabama history is a history of brutal bigotry, but it is also a history of hope and perseverance. These two things cannot be removed from one another; they are two sides of the same coin.

Examples of this can be seen on our own campus. In 1963, Governor Wallace stood in front of the entrance of Foster Auditorium to prevent two Black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from registering for classes as he was cheered on by white students. In this single event, there are two vastly different stories to be told. The hatred of Wallace and the students on one hand, and the perseverance and courage of Malone and Hood on the other.

To those of you who argue that Alabama should embrace its history, I would agree, but I contend we should embrace our history of hope, not our history of hate.

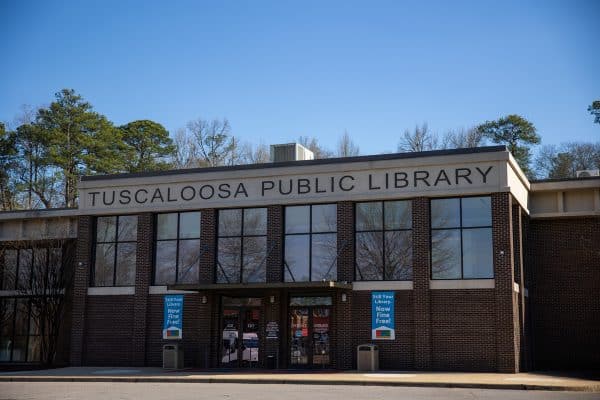

It is with that frame of reference that I started to think about B.B. Comer Hall. It is the yellow brick building across the Crimson Promenade from the Student Center. It is named after Braxton Bragg Comer, who served as governor of Alabama from 1907 until 1911. While in office, he was responsible for increasing appropriations for higher education. The plaque inside B.B. Comer Hall celebrates him as a “a distinguished citizen” whose “enlightened and liberal support made possible a greater university.”

Comer’s legacy is not only that of a champion for higher education. It is stained, like many Alabama politicians, with abhorrent actions and policies.

Comer’s family rose to prominence in Barbour County, Alabama, becoming rich off the back of slave labor during the Antebellum era. After fleeing Alabama during the Civil War, Comer returned to help run the family’s plantation and Avondale Mills, a textile manufacture which utilized child labor.

Comer also became a prominent leader in the White League, a white supremacist terrorist organization. Comer was named as a leader of the mob responsible for the Eufaula Election Massacre of 1874, in which at least 15 Black voters were killed and another 100 were injured.

Additionally, Comer served as governor during the 1908 miner’s strike. During which, a Black labor leader was lynched by a mob. Referencing the strike, B.B. Comer was quoted as saying: “We are outraged at the attempts to establish social equality between black and white miners.” He added that he would “not tolerate eight or nine thousand idle n****** in the state of Alabama.”

Comer would go on to lose a re-election bid in 1914, and he receded out of the statewide consciousness, never to return in any meaningful capacity. A building on our campus remains as one of the last remnants of a long forgotten governor.

As Thomas Paine famously said, “a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it the superficial appearance of being right.” B.B. Comer’s obscurity as a political figure allowed the building named in his honor to remain unchallenged to the present day.

That is, until 2020. Throughout 2020 and 2021, the UA System board of trustees renamed several buildings that did not align with the “shared values” of the board and the University. While they considered changing B.B. Comer Hall’s name, the building’s name remained unchanged.

Whether by ignorance or by malpractice, the board of trustees ignored the legacy of hate B.B. Comer left in his wake. This truly begs the question of what exactly the “shared values” are that the board claims to defend, if a man like B.B. Comer can still have a building named after him on our campus.

Alabama’s history should not and cannot be forgotten. We should not pretend like B.B. Comer and people like him never existed. Without the ugliness of Alabama’s history, it is impossible to appreciate its beauty, but it is possible to do that without framing people like B.B. Comer as worthy of praise. B.B. Comer is not deserving of glorification.

His name should be synonymous with hate, not a building. We should not force students to walk halls in any way associated with such an objectively bad person. The University of Alabama has a choice. It can continue to embrace Alabama’s hateful history, or it can turn away and embrace a history and future of hope.

The choice is clear. The University of Alabama should rename B.B. Comer Hall to a name more in line with the values the University claims to hold.