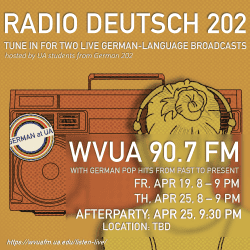

‘Empty fields and parking lots’: Alberta still bears scars from 2011 tornado

Alberta City residents and business owners say they were left out of major rebuilding after the storm.

Alberta City, captured above by a drone, now features empty lots where homes and businesses once thrived. Photo courtesy of Alexander Mobley

April 14, 2021

The city rebuilt the Schlotsky’s and the Taco Casa. The ducks have returned to Forest Lake. Historic Hargrove and Hackberry neighborhoods have been restored, save the live oaks that once gave Druid City its name.

But nearly a decade after the destruction, one of Tuscaloosa’s hardest-hit communities still struggles to recover.

April 27 will mark 10 years since a deadly tornado with winds upwards of 190 mph ravaged Tuscaloosa, destroying 12% of the city, and claiming 64 lives in its path. At its apex, the tornado was more than 26 football fields wide.

The tornado that bore down on Tuscaloosa was rated an EF-4 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale, a standard used by meteorologists to determine the strength of a tornado. The tornado strengthened as it crossed the Black Warrior River into Tuscaloosa, and it tore straight through well-developed commercial districts of Tuscaloosa. Debris cleanup in the city alone cost $100 million.

While many of the neighborhoods in Tuscaloosa that were affected by the tornado, such as 15th street and McFarland Boulevard, have been redeveloped, other areas of Tuscaloosa still remain bare in comparison.

At least it was a flowing community before the tornado. Now, it’s just empty fields and parking lots

— Karen Mathis

Tuscaloosa’s Alberta suburb, which makes up about one-fifth of the city’s population, faced particular devastation from the tornado. Up to 60% of Alberta was destroyed by the tornado, including Alberta Elementary School. Alberta’s iconic Leland Shopping Center was also damaged beyond repair. Centers of Alberta’s community were also affected by the tornado. Former President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama visited Alberta City and Holt on April 29 following the tornado outbreak.

Census data shows that six years after the tornado, nearly 1,000 residents had left greater Alberta, which was home to about 20,000 people. And while new apartment complexes and developments have sprouted closer to Tuscaloosa’s midtown area in the past few years, community leaders say the heart of Alberta City still struggles to retain businesses.

April 27, 2011 was a Wednesday, and the congregation at Chapel Hill Baptist Church was getting ready for that night’s service.

“We were planning to have a bible class that evening. With the bad weather, I decided to cancel the service,” Kelvin Croom, reverend of Chapel Hill, said. “You know the end result. We had to demolish the church, and it was devastating.”

With Chapel Hill’s building completely destroyed, Croom said that he reached out to the University Church of Christ, which allowed the Chapel Hill congregation to use one of their rooms for worship services.

“That happened on a Wednesday, and that Sunday, we had our first worship service at [University Church of Christ]. We never missed a Sunday of having worship service because of that tornado,” Croom said.

Today, much of what used to be residential and commercial spaces in the suburb remain empty and undeveloped. According to the National Weather Service, many of the homes destroyed in Alberta used cinder-block construction, and in some cases, debris was swept away completely.

“Alberta could have always used a pick me up,” said Karen Mathis, owner of Bama Tan in Alberta. “But at least it was a flowing community before the tornado. Now, it’s just empty fields and parking lots.”

When the April 27 tornado tore the front off of Bama Tan, Mathis, who now owns the store, was just a manager. The business received a renovation permit, and was able to reopen after six months. Mathis said after the tornado, she applied for a grant through the Tuscaloosa Small Business Revitalization Loan Program to open her own full-service salon in Alberta, but her application was denied.

“We got to build back quicker than some [businesses],” Mathis said. “And some never recovered.”

The revitalization program was opened as a result of the April 27 tornado. It provided two types of loans to businesses in the Tornado recovery area. A commercial revolving loan program gave businesses a zero-interest loan. Businesses that were thought to be able to repay the loan were prioritized, and would resupply the fund so that other businesses could recieve loans later, according to the Tuscaloosa News.

By the application deadline for the revolving loan program, only four businesses across the city had applied for $780,000 of the $2.5 million available under the program. Another type of assistance loan given to businesses in the recovery area acted as a grant, and didn’t have to be repaid as long as the recipient business stayed compliant.

Tuscaloosa reopened the Small Business Revitalization Loan Program in October 2016 with leftover funds. The city doesn’t currently offer any business assistance programs.

Businesses on the strip here have been left abandoned.

— Kristie Jackson

Like Bama Tan, Chapel Hill was also unable to benefit from financial assistance and grants.

Croom said that while Chapel Hill Baptist Church was able to qualify for a grant from the City of Tuscaloosa, they were unable to receive the grant due to the source of its funding.

“With the funding coming from the federal government, we could not use [the grant] because of the separation of church and state,” Croom said. “Of course, we are a church. I couldn’t lie to people and tell them we’d never have bibles in there. So, we did not get that money.”

After 2011, Chapel Hill’s congregation worshiped in various temporary facilities across Tuscaloosa, including the Belk Activity Center, the McAbee Activity Center and the University Church of Christ, while waiting for their own campus to be finished.

Croom said that in 2017, Chapel Hill “moved back into our own site, which we called the promised land.”

Croom said that the redevelopment of Alberta’s residential communities has been steady, but that “a lot of it, you don’t see around University Boulevard.”

The Alberta section of University Boulevard is scattered with unused lots, fields and parking lots – places where businesses and shopping centers used to be – that have not housed any type of development since the April 27 tornado.

Mathis said issues with Alberta’s infrastructure could be to blame for the low number of businesses moving into the area.

“I think that if they would enhance the sidewalks and general area, then it would be a more appealing place for businesses to venture into,” Mathis said. “Once you cross into Alberta, you can see that it just becomes bland.”

Some newer businesses that have opened in since the tornado also struggle as a result of conditions in Alberta.

Kristie Jackson, the owner of Druid City Vintage Vendor Market in Alberta, said “a lot of businesses didn’t get to build back, and a lot of properties are still vacant and unused.”

Jackson was able to open her vintage shop in 2016, with financial assistance from the Small Business Revitalization Program.

Although the city has installed new sidewalks throughout parts of Alberta, the new sidewalk construction was stopped short of Druid City Vintage-Jackon’s vintage shop.

Jackson said the lack of sidewalks in front of her business has not only affected her stream of customers, but that for pedestrians “it’s a very dangerous area to walk without a sidewalk.”

Tuscaloosa City Council Member Kip Tyner said many of the businesses destroyed in Alberta during the tornado were “mom and pop shops” that couldn’t afford to rebuild.

Tyner said the recovery in Alberta has been “one block at a time,” and that the biggest obstacle in bringing businesses back to Alberta has been land prices.

“There were a lot of rumors that the University of Alabama was going to buy up a lot of the property and move that direction,” Tyner said. “So people naturally tried to get as much money for their property as possible.”

According to the Census Bureau Statistics, as of 2011, the median housing value for owner-occupied homes for the city of Tuscaloosa was $154,300 and the median household income, $35,304, with 28% of the population living in poverty.

Tyner said the tornado resulted in a population exodus from Alberta, and that the community’s population decreased significantly after April 27. Alberta experienced the largest loss of life in Tuscaloosa as a result of the tornado.

“We lost so much of our population. A lot of the vacant land that you see were homes,” Tyner said.

Tyner said the decrease in Alberta’s population has made bringing new developments to the community even harder.

“One major issue is traffic counts,” Tyner said. “You have to have traffic counts to attract business.”

Tyner said the construction of the University Boulevard bridge in Alberta, which lasted between January 2013 and November 2015, kept traffic counts low and “was a killer” for bringing new developments into Alberta.

“After we returned to a little normalcy, there was no traffic,” Tyner said. “I cannot tell you how many businesses backed out because of the bridge.”

In November 2019, German engineering company SWJ broke ground on it’s new North American headquarters in Alberta, after receiving $250,000 in economic incentives from Tuscaloosa, according to the Tuscaloosa News.

Tyner said SWJ will provide Alberta with 115 “high-paying, high-tech jobs,” and described SWJ’s decision to locate in Alberta as “a major domino,” adding that the SWJ facility “gives amazing credibility to Alberta” that could attract new businesses to the area.

The SWJ headquarters is located next to the Alberta School of Performing Arts and the Gateway Digital Library, in one of the most heavily revitalized portions of Alberta. Just down the street from the SWJ are a series of empty parking lots that used to house local businesses like the Leland Shopping Center, Leland Lanes and Wright’s restaurant.

Some members of Alberta still want to see more for their district.

“Businesses on the strip here have been left abandoned,” Jackson said. “We need some financial assistance in this area, making it easier for people to rebuild businesses or start new ones.”

Croom echoed the need to not only revamp but to overhaul Alberta.

“We would have liked to have seen the development of the train station,” Croom said, referencing a deal between Tuscaloosa and Norfolk Southern for a new train station in Alberta that fell through in 2019. “We are faithful that things will come, and that the old Leland Shopping Center will be developed. We are hoping that others will find interest in this community.”