Black History Month program kicks off with panel, campus dialogues

February 6, 2020

In light of the upcoming 2020 election, this year’s Black History Month (BHM) programming is aptly themed, “African Americans and the Vote.”

University groups officially kicked off BHM programming on Wednesday, Feb. 5, with a dialogue on “Black History and the Black Experience at the Capstone,” as well as a panel discussion on race- and class-based inequality, along with ongoing educational efforts and exhibits by UA students and faculty.

MONOPOLIZING WEALTH

Crucial discussions about intersectionality, community building and dynamic gameplay took place Wednesday, Feb. 5, in the basement of John England Jr. Hall.

From noon to 1:30 p.m., the Division of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion hosted the “Monopolizing Wealth: Understanding Race- and Class-Based Inequality” lunch and learn, as groups of UA students embarked on a rousing game of Monopoly with a few new rules.

Each player got a number between one and six; along with that number came a set of rules that restricted what they could purchase in terms of property, how much money they started with and how much they got when they passed Go, with number one being the only number that was allowed to do whatever they wanted.

Participants played by these rules for the first 40 minutes of the game and then were told that they could then play just like it was a regular game of Monopoly, but the trend of player No. 1 dominating the game persisted. After 20 more minutes, the game ended, and a discussion led by Wanda M. Burton, assistant professor in the College of Human Environmental Sciences, began.

She started by asking the participants their thoughts on the game. Students expressed their frustrations with how hard it was being heavily restricted and how they hoped the game would be equal, even though they had been told what the game was about.

“Even when it became everyone could buy anything, so like when we reached equality, we still couldn’t really buy anything because the ‘ones’ already had everything,” one student said.

Burton then inquired about the game’s real-world implications.

This prompted another student to bring up the concept of redlining, which is the act of hindering access to resources for certain groups of people in areas based on race or ethnicity, in reference to the game’s rule about certain people not being able to purchase past property rows one and two.

“I could only buy property on row one, and I still felt like a lot of it got bought up by the people with more money off the bat,” one student said.

He said it reminded him of gentrification because the people with more money and privilege were able to do whatever they wanted with the property.

Another participant said after the game achieved “equality,” she was stuck in the mentality of not being able to do anything.

“You really felt that the discrimination you had felt started to get inside, and it limited your ability to play the game even though the rules were equal,” she said.

Another woman came to the conclusion that “it’s only truly fair if everyone starts out with the same rules at the very beginning of the game.”

CAMPUS DIALOGUES

Campus Dialogues is part of a weekly programming initiative by UA Crossroads to foster discussions about issues on campus. On Wednesday, groups of students discussed a variety of topics related to black experiences at the University, ranging from expectations in classroom space, to building names, to campus tours.

Breana Miller, a junior majoring in psychology, was always proud of her history. Her grandfather, Frank Wiley, was a principal who helped integrate schools in her Georgia town, and his legacy was something her family worked to keep alive – even when her schools and the town’s archives avoided it.

“When I was a kid, I thought – I still think – being black was cool,” she said. “It was always so cool to learn about the impact that my people and my ancestors had, on my hometown, on my country, on my state, on the world.”

Miller said that, though welcoming different perspectives might be uncomfortable for some students used to a dominant narrative, discomfort can cause change.

“A lot of times, for black students, we’re the only ones in some of our classes,” Miller said. “Sometimes we have to be the loudest person speaking because we’re often going to bring perspectives that weren’t thought of before.”

Miller pointed to her shirt, which had the words, “If only we loved black people as much as we love black culture” printed against a light-pink background. It reminded her of the University’s ability to draw in large crowds to watch a majority-black football team play, while black scholars sometimes lack recognition.

“If only you loved us for the abilities that we possess and the culture that we have, why can’t you love us for us, and for our experiences?” she said.

Darnell Sharperson, a senior majoring in public relations and president of the Black Student Union (BSU), opened the conversation with a speech about the importance of understanding black experiences as something that is individual, not monolithic.

The mission of BSU is to educate, advocate and celebrate the black student experience. Every year the student union hosts a BSU week, where Sharperson said the group will be highlighting voter registration, including a screening of “Rig: The Voter Suppression Playbook” and co-sponsoring a cultural excursion to The Legacy Museum in Montgomery.

Sharperson said raising awareness about voting registration for the next generation of leaders is incredibly important, but especially for African American students.

“A lot of the times, their voices aren’t heard, and we face additional adversities when it comes to registering to vote and things of that nature,” Sharperson said. “I think it’s necessary to start that conversation, because I think a lot of people don’t know that certain barriers have been put in place to keep students like us from voting.”

Miller pointed to the work by historians like professor Hilary Green in highlighting the campus’ history of racism, but also of the black individuals who resisted that racism.

“I think there needs to be a common understanding that black history is world history,” Miller said. “It’s American history. It’s men’s history. It’s women’s history. We were there. We are there. We are still making strides.”

SAY THEIR NAMES

It’s common practice for Twitterstorians to utilize Black History Month as a valuable teaching moment. For Green, an associate history professor in the department of gender and race studies, the lessons are local.

On Feb. 1, Green launched a Twitter campaign to educate followers on the University’s history of slavery.

“Why does Black History Month matter in 2020?” Green said in a tweet. “We still need to continue Woodson’s charge of countering the historical propaganda promoted against people of African descent. Education. Being present. Speaking the truth remains necessary.”

Each day, Green highlights an enslaved worker on campus: Ben, who labored around the campus’s first phase of construction; Moses, who assisted professor Michael Toumey with collecting geological specimens for a state survey; William and Briggs, who constructed the dome on Maxwell Hall; and Johnson, who laid brick for the observatory. Throughout February, the list will go on, highlighting the names of those who built this campus.

“The history and unacknowledged contributions of these men, women and children matter and deserve recognition over these 29 days and beyond in the continuing slow campus conversations of how to reconcile its slave past and complicated racial legacy,” Green said at the bottom of the thread.

The project, which was inspired by a Georgetown University initiative and derives from archival research that Green began in January 2015, is just one of Green’s efforts to bring black history on campus to light. Green, the pioneer behind the Hallowed Grounds Tour, also offers an alternative campus tour highlighting the University’s connections to slavery and segregation, which will continue throughout February.

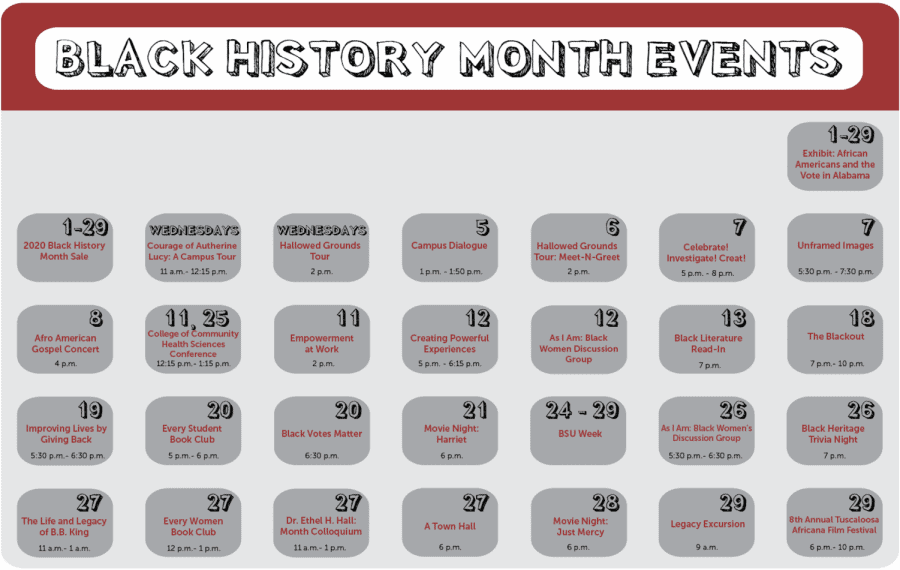

To learn more about Green’s work, or to book a tour, visit hgreen.people.ua.edu and follow #slaveryua on Twitter. Find a full calendar of Black History Month programming at crossroads.ua.edu/black-history-month/.