University DEI ignoring Native Americans, Native students say

March 29, 2023

Despite the University’s recent success with its diversity, equity and inclusion measures meant to increase enrollment and retention among certain minority groups, it has faced unchanging enrollment and retention among Native American students, which remain disproportionately low. To some Native American students, it feels as if DEI measures are just “checking a box.”

Last fall, the University reported having enrolled the greatest number of students of racial or ethnic minorities in its history, 8,542, including a record 4,344 Black and 2,138 Hispanic undergraduate and graduate students.

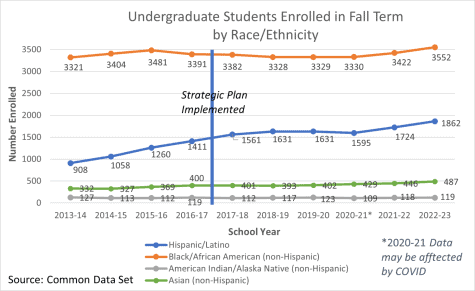

According to the Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, over the 2019, 2021 and 2022 fall semesters (excluding fall 2020 due to COVID-19) undergraduate numbers for non-Hispanic Black students increased from 3,329 to 3,422 to 3,552 and from 1,631 to 1,724 to 1,862 for Hispanic/Latino students.

Meanwhile, the number of enrolled undergraduate Native students, which the University classifies as “American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic,” comprise just 0.367% of the University’s 32,458 undergraduates as of last fall. Including graduate student numbers, there are currently 134 Native students enrolled, or 0.35%.

Nationally, just 0.637% of all post-secondary students were Native as of fall 2020. 2020 Census data shows that the non-Hispanic/Latino Native population makes up 0.46% of Alabama’s population and 0.679% of the U.S. population.

Seniors Kiana Younker and Katherine Johnston are the co-presidents and co-founders of the Bama Indigenous Student Organization Network, which works to make the University more accepting and understanding of Native students and culture. They are members of the Coquille Indian and Caddo tribes, respectively.

“When I came here, it was so hard because I did not know a single other Native student. I had no way to relate to anybody else. … It … wrecked me,” Johnston said.

It took Younker and Johnston until their third year at the University to meet one another, the first Native student each had met on campus.

“There’s nobody here that looks like me, talks like me, acts like me. … When you … come from a different cultural background, it separates you more from the collective,” Younker said.

Shane Dorrill, assistant director of communications for the University, declined to comment about what the University believes to be the cause of low Native student enrollment.

Retention rates are also disproportionately lower for Native students at the University compared to other demographics. According to the OIRA, for the class of 2025, the second-year retention rate among Native students was 64%, the lowest of any racial group.

These statistical disparities have not gone unnoticed by the University.

In 2016, the University unveiled its “Strategic Plan” to improve, among other unrelated things, diversity, equity and inclusion on campus from 2017-2021. The plan called for the establishment of a DEI officer position, later called vice president and associate provost of DEI, which inaugural officer G. Christine Taylor accepted in 2017.

In 2020, President Stuart Bell convened an advisory committee, which Taylor spearheaded, to update the plan with new “Path Forward” strategies to promote DEI. The advisory committee consisted of 13 members; Taylor declined to comment on if any of the members were Native Americans.

According to Taylor, the University OIRA defines “underrepresented” students as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latino and/or at least one the following races: Native American, Black, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

“As we implement Path Forward, we focus on enhancing our efforts with underrepresented and minority groups as a whole rather [than] by segmentation of populations by race, ethnicity and other factors,” Taylor said.

Yet, data from before 2016 shows that the strategic and Path Forward plans have not improved enrollment or retention of Native students.

Fall undergraduate and graduate Native enrollment averaged 147 students from 2011-2016, prior to the strategic plan, according to the OIRA. This average decreased to 139 from 2017-2021, excluding 2020 due to COVID-19.

Effects of Low Enrollment

“Being the only Native student in a class, in a residence hall, or even on campus in a mainstream institution is a common and overwhelming experience,” wrote the American Indian College Fund, a charity that serves to advance equity for Native students in post-secondary education. “Students experience racism, isolation, invisibility, and ignorance. This fractures their sense of belonging and can cause students to take time off from or quit school.”

According to the AICF, perceived invisibility “is in essence the modern form of racism used against Native Americans” and is the driving factor behind poor college access and completion rates among Native students.

“Sometimes it’s overwhelming [feeling invisible]. It is so very hard to try and speak and share and truly connect with others when some aren’t open to hearing or they just don’t understand,” Johnston said. “I wear my jewelry and my clothing and I’m the only one.”

A report from the Reclaiming Native Truth project highlighted a study from 2017 that found that “a major challenge [to Native American equity] is ‘the invisible Indian,’” as 62% of Americans who live outside “Indian Country” reported being unacquainted with a Native American.

Amber Manitowabi-Huebner of Wiikwemikoong First Nation is a UA distance-learning graduate student studying population health sciences after graduating from Northern Michigan University. She identifies as “half-white, half-Native.”

“I played basketball in undergrad. … I had a coach that said, during the 2020 [racial tension], … ‘We’re lucky we don’t deal with that, because everyone on our team is white.’ And I felt like that was a hurtful thing to say. … And my teammate thought it was funny to call me ‘chief,’” she said.

Outreach and Recruitment

The AICF outlined targeted outreach to Natives as a necessity to remedy low enrollment.

“Today, many institutions limit their recruitment to readily accessible populations or ignore Native populations entirely,” it said.

Taylor and Dorrill declined to comment on if the University conducts targeted outreach to Native students.

“UA has not pursued outreach the way it could,” said Mairin Odle, a professor of American studies at the University. “Historically to this university, like a lot of other institutions, Native people tend to fall into a gap of visibility. And the University is not looking, and therefore they’re not measuring.”

Manitowabi-Huebner said other schools go the extra mile to recruit Native students.

“When I was in South Dakota, I saw a recruiter at a powwow. It was a Lakota language summit. And they were just … giving away free pens and kind of giving people the idea that they care, … [that] our recruiters are stepping into your comfort zone,” she said.

“The University of Alabama is committed to enriching our learning and working environment by attracting, welcoming, and supporting all faculty, staff, and students through inclusive excellence,” Dorrill said.

Financial Aid

“The most common reported reason that people don’t finish a degree is because of financial reasons,” Odle said.

As such, the AICF advises institutions to provide significant financial aid to Native students.

Native people face the highest poverty rates of any race in the U.S. at over 25%; however, the AICF views financial aid as necessary for its ability to “right the wrongs of past discrimination,” through scholarships, grants, in-state tuition for members of federally recognized tribes, or tuition waivers.

“A lot of [western institutions], if you’re part of a federally recognized tribe, offer completely waived tuition,” Younker said. Recently, the University of Arizona began offering waived tuition to members of the state’s 22 recognized tribes.

Despite offering over $33 million in scholarships and fellowships from Sept. 30, 2021 – Sept.30, 2022, as per the University’s financial report for that year, there are currently no scholarships specifically for Native students attending the University. When asked if the University offered automatic or merit-based scholarships to Native students or if it planned to do so, Dorrill cited the University’s diversity merit scholarships, which awards Black, Hispanic, Native and rural students.

Native Programming and Physical Space

Students say the University is failing current and prospective Native students in other ways as well, as it is not listening to other recommendations by Native experts and the students themselves.

Robin Zape-tah-hol-ah Minthorn, a Native professor at The University of Washington Tacoma who studies Native challenges in education, said to support Native students better, institutions must create safe spaces for Native students and acknowledge the history of Native people on campus and the fact the institution lies on their ancestral land.

Younker believes a major hindrance for enrollment specifically is a near-complete lack of official programming offered for Native students.

“Prior to BISON’s creation, there was zero Native programming on campus. The only Native programming that happens [is] during Native American Heritage Month [in November] in the Intercultural Diversity Center. One month a year. And that’s it,” Younker said.

The CW was only able to find records of University-sponsored events in recent years that occurred during or around that time.

BISON was established last fall and has held events for Native students throughout the year.

“As students, there’s only so much we can do by ourselves,” Johnston said. “There are some times that [BISON] really feel supported by certain departments such as the IDC. And there’s so many people working to open doors for us.”

“In other instances, it’s like when we’re included in things … it’s trying to check that box … match that quota,” Johnston said. “It’s like … we thought there weren’t Native students here. Now there’s a Native student group. Let’s check that box that we are representing all minority groups for DEI but let’s not go further than that.’”

Taylor declined to comment on if the University planned to create such physical spaces for Native students, deferring to the Office of Student Life.

“There are many universities that have worked hard to have programs and safe spaces and physical spaces for Native students,” Johnston said. “I never expected when coming here with the history that there would be so little.”

Acknowledgement of Native History on Campus

Younker and Johnston said that the University fails on the point of acknowledging Native history and ties to the University’s land, despite Tuscaloosa being located along the Trail of Tears, the deadly route taken by Native Americans when they were forced to abandon their ancestral lands and move to Oklahoma.

Odle previously told The CW that the University was built on land that belonged primarily to Choctaw and Creek tribes, but UA is not unique among U.S. universities in having been built on Native land.

“But the University and Tuscaloosa … [are] on lands that were in some cases purchased through land deeds and other cases through really outright theft from Native nations,” Odle said.

The lack of attention brought toward Native history, Johnston and Younker said, is most apparent in the University’s omittance of a land acknowledgment to the tribes, such as Johnston’s, wherein the University would publicly state its awareness of the fact that it is built on the ancestral lands of the tribes who were forcibly removed on the deadly Trail of Tears or by soon-to-be-broken treaties.

“The [UA] administration is aware and has discussed the desire for a public land acknowledgement. At this time, an official acknowledgement has not been approved,” Taylor said in an email, declining to comment on why it has not yet done so.

“To come … back to my tribe’s homeland in Alabama, I was so excited because … this is full circle for my family. … And then to look around and for there to be no acknowledgment that we were here breaks my heart,” Johnston said.

The University has previously acknowledged major campus events that occurred during the Civil Rights Era via its construction of the Autherine Lucy Clock Tower and Malone-Hood Plaza in 2010, which commemorate the immense difficulties faced by the first Black students admitted to the University. Historical markers on campus additionally marks sites such as the site of the “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door,” whose historical marker was created in 2004. These came after years of push by activists, particularly the “We are Done” movement, for the University to acknowledge such history.

Younker and Johnston, however, have expressly asked the University for a land acknowledgment but been unsuccessful.

Looking to the Future

“The work of developing a more inclusive and welcoming community is a culture change process,” Taylor said. “Our campus has formally been on this journey for only five years. Since that time, a lot has been accomplished, and there is certainly more work to be done.”

Johnston and Younker said that their efforts to create BISON have been a step in the right direction toward improving the Native student experience.

“BISON has improved my college experience dramatically,” Younker said. “It allows me to be a leader. It allows me to set boundaries with UA on what is appropriate and what is not if they ask, which most of the time they [do]. It allows me to bring more culture to this campus … and more awareness.”

The pair said the University must make a commitment to its Native students if it wants greater change.

“They’re always asking … ‘Oh, why don’t we have a diverse campus?’ Well, you don’t create the opportunities for BIPOC people to come here and feel safe,” Younker said.

“When a school doesn’t recruit or offer support in any way or acknowledgement or have anything geared specifically towards … Native students, it makes it even harder to step outside of your comfort zone and to dream and to go to school [for them],” Johnston said. “When [our intergenerational] hurt is invalidated and not acknowledged, and when [our] extra needs are not addressed, it changes everything.” And to know that and to not be able to fix everything in a heartbeat breaks my heart.”